What happens when we die (#19)

For the most vulnerable, the unfortunate answer is capitalism, apparently.

One of the best things about social media platforms like TikTok is we get to know and learn the stories of soooo many different people, who we might’ve never known about otherwise. Arguably, this trait is also the worst thing about social media. Case in point: 21-year-old bones influencer Jon Pichaya Ferry, who calls himself “Jon Jon” and frequently posts about his exhaustive human bone collection on the app. His interest in osteology — the study of bones — has garnered nearly 500,000 followers on TikTok as well as a sizable following on Instagram and YouTube. But it has also raised questions about his human bones-supply business (yes, really), the ethics of its operations, and the mistreatment toward those most vulnerable to exploitation, even when they are no longer here.

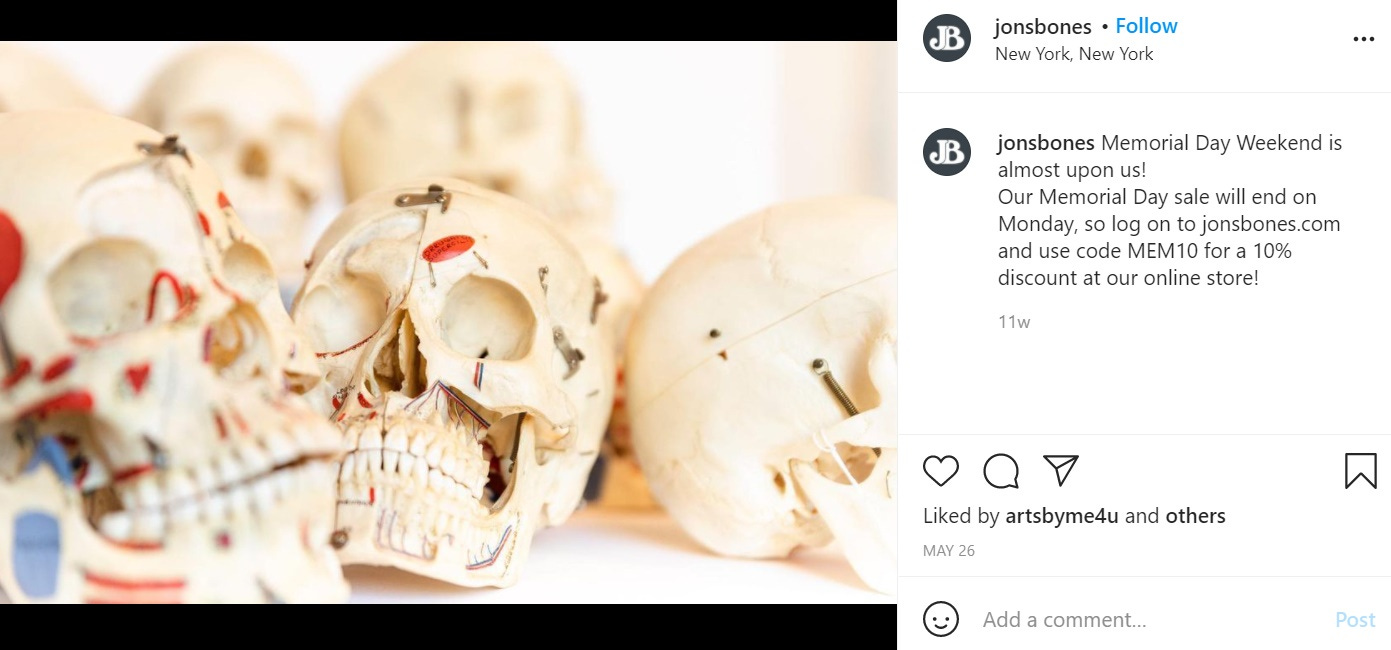

As the profile of Ferry’s company, JonsBones, grew so did the scrutiny around his, um, sizable bones collection. He often shoots his TikTok videos (which, like most influencers, basically function as marketing ads for his brand/company) in his “showroom,” a nice large space FILLED with human skulls and bones. Reasonably, this sparked a lot of questions from people, such as “where did you get all those human bones”, “are these real”, and “is this legal???”

While what he does is in fact legal — there are no federal laws against trading human bones in the U.S. except when it involves Native American remains, though there may be local laws against it in some states — his attempts to answer questions regarding the sourcing of his “products,” which sell for upwards of $6,850, have backfired. In one video, Ferry admits that the origin of the company’s supply was probably India, likely from the Dalit which is the lowest caste in Indian society (additionally, some users posted screenshots from the website of a skull that belonged to a Sámi, the Indigenous people living in the Nordic territories. The product seems to have been taken down). In other words, these were real remains that belonged to marginalized people, making how these bones were retrieved highly questionable.

Despite online backlash — including from those who study/professionally work in osteology-adjacent fields — Ferry maintains the bones are “responsibly sourced,” simply because “our bones are certified bones from the medical trade” or secondhand bones bought from medical folks or people who inherited them from family who worked in medicine. But is that a strong enough argument to say what the company is doing isn’t ethically questionable? If you look at the history of the bones trade industry, probably not.

From the 19th century until as recently as the early aughts, the bones trade was a booming business with a pipeline that primarily came from India. In earlier centuries, human remains for medical studies were difficult to come by in western countries like the U.S. and the U.K. but demand for them rose as medical research advanced.

According to the University College London’s blog, western christianity played at least some part in making the idea of providing and/or dissecting human bodies taboo, which led to a prevalence of grave robbing to satisfy the research field’s demand for human remains, resulting in conflicts between grieving families and grave robbing suspects. The U.K. government tried to address this issue through the Anatomy Act of 1832 which allowed doctors to use unclaimed bodies from the morgues for research purposes. Still, it wasn’t enough to meet the medical industry’s market demand.

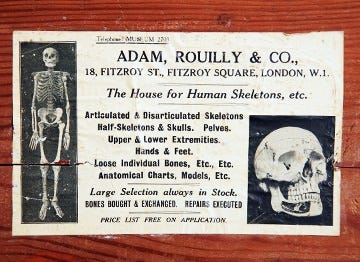

British companies like Adam,Rouilly (a company which Ferry, the Insta-bones dealer, by his own words is incredibly enamored with for whatever reason) began turning to the colony of India for their “products.” That led to a booming trade in human remains largely supplied by India. The country got really good at processing and preparing the bones just the way supply companies preferred them — scrubbed to a pristine white and constructed with high-quality connecting hardware — so India became the primary source for North American and European companies. But how these bones were harvested was — and still is — sketchy AF.

Most skulls either came from poor Indian families who had no money to cremate their loved ones, vagrants who died on the streets, or from grave robbers who dug up the cemeteries. This, of course, was no concern to the western medical supply companies, which happily purchased the bones to sell for a profit overseas, brandishing them with their company logo to “certify” the remains (again, there are no regulations on trading in human bones, at least not in the U.S.). As the UCL article notes (emphasis mine):

There are some elaborate 18th and 19th century trade cards for ‘skeleton suppliers’, such as Nathaniel Longbottom of St Thomas’s Street Southwark. Although this indicates that you could go and buy a human skeleton from a shop, there is no indication as to the original source of the skeletons. Of course they may have acquired them in completely legitimate circumstance, but the likelihood of body donation at this time is unlikely.

The demand for human bones for medical research continued into the late 20th Century. The Chicago Tribune reported that India exported about 60,000 skulls and bones in 1984 alone — that’s A LOT of human bones! The Indian government banned the export of human remains in 1985, but reports have found that a black market has persisted since. Before the 90s, medical schools in the U.S. required students to use real human bones to work on, propping up the market’s demand. According to a 2007 Wired report, the bones business boom created commercial products like combo kits containing medical textbooks plus human bones, which sold for $300 a pop:

Sixteen years after the export ban, it was as if the law had never taken effect. “We used to fill orders all over the world,” says a clerk employed by Young Brothers between 1999 and 2001, who requested anonymity. “We used to buy bones from Mukti Biswas. I saw more than 5,000 dead bodies.” There were other suppliers, too, and factories up and down the length of West Bengal. The company took in roughly $15,000 a month.

Given this seedy history, it’s difficult to disconnect JonsBones’s business from the dark origins of the bones trade industry. Even if Ferry thinks his company’s work is kosher because — ignoring for a second the fact that he’s profiting off commercially selling people’s remains — he only buys from certified medical sellers, we know the majority of these “products” were originally sourced inhumanely from minorities and marginalized people. But really, the issue goes deeper than one famous TikTok Zoomer or even the international bones trade.

Earlier this year, the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton were embroiled in controversy after it was discovered they had mishandled the remains of two children killed in the 1985 government-sanctioned bombing of the house of MOVE, a Black advocacy and revolutionary organization in Philadelphia. It turns out, the remains of sisters Tree (14) and Delisha (12) had stayed in the possession of a researcher who was tasked to identify them, unbeknownst to the surviving family. The children’s remains were then moved back and forth between universities and even used as a “case study” in Princeton’s online course. Now the universities claim they don’t know where the remains are, basically shrugging off their negligence.

Modern science has a well-recorded history of bigotry, racism, and colonialism. As Michelle Rodrigues, an assistant professor at the Marquette University, wrote for the publication Sapiens, that history has dehumanized people of non-white origins, particularly when they are the subject of study. She describes her own uneasy feelings as a teaching assistant handling the human remains of a subject who shared her physical traits:

I learned from my professor that Number One was known to be female, of South Asian origins (like me), and possibly Pakistani. Other students remarked that she was tiny, but I realized that most of her bones were the same size as mine. Her clavicle was the size of my clavicle; we matched. Her cranial bones were zippered together with a wide dark line, which meant she was a young woman: old enough to have finished growing but too young for the bones to knit together and the lines to soften. Perhaps she had been in her late teens or early 20s. I was 25 at the time.

Part of the problem is that scientists are often trained to maintain a certain emotional distance from their objects of study, which can be helpful when dealing with sensitive or difficult work. But part of the problem, too, is that White Europeans and their descendants have often historically seen people from other places in the world as less than human.

The question of ethics in science is messy, but it’s become a big discussion in academic forums and papers. It’s come up a lot especially in the field of archaeology where researchers studying ancient cultures and artifacts contend with the less delicate methods of their predecessors: white men from colonizing countries operating at a time when it was totally chill to steal cultural relics or slice open an Egyptian mummy — which, when it comes down to it, is essentially a person’s disturbed burial — in the name of science. Let’s hope that growing resistance against these types of scholarship leads us to a place where we can excavate knowledge without disturbing the dead.

WANT TO LEAVE YOUR DESTABILIZING COUNTRY? FIRST, YOUR VISA

The weekend brought major developments in the war in Afghanistan as the country’s capital was overtaken by the Taliban. The capital city of Kabul fell to the insurgents on Sunday, causing a mass evacuation response (if you’d like to understand the gist of how the last week of the Taliban’s insurgency unfolded across the country, here’s an explainer I wrote for Vox).

As updates flooded my Twitter timeline, what struck me most were reports of foreign embassies and consulates trying to expedite visa applications to help get their Afghan support team out of the country. I saw some comments online commending these brave souls risking their safety to save the Afghan people, so to speak. I found these accounts shallow and frustrating. To me, people trying to flee a crumbling country getting caught up in immigration bureaucracy is not a feel-good story!!

It’s no secret that Afghans who’ve worked with foreign government entities in positions like embassy staff or military interpreters are most at-risk of retaliation should the Taliban choose to get rid of people they see as enemies of the new state (those who hold other critical occupations such as journalists are also at-risk, prompting news organizations to advocate for government support in getting them out of safely). That these people are now being held back by cursed immigration bureaucracy, despite all their work for these foreign governments, is appalling. Meanwhile, American service dogs are literally given priority seats on evacuation flights.

Some didn’t even try to pretend they cared about the Afghans they worked with and abandoned their teams altogether. Sweden and Holland quietly closed their offices without so much as a word to local staff, who found out officials and foreign staff members had left when they came in for work and nobody was there.

The likelihood of the Taliban assuming power as the U.S. military withdrew was a scenario anticipated since a year ago when the Doha agreement finalized the complete pullout of American forces and allied troops. For those directly involved in the war, the calamity that would result from an abrupt exit seemed obvious even a decade ago.

Beyond that, the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program for Afghans, which first launched in 2009, has long been plagued by extreme backlog and abysmal record-keeping that was known but never addressed by the U.S. government. For Newlines Magazine, Leila Barghouty reported on the program’s incredible dysfunction:

It’s a “perfect storm” of dysfunction on all levels, Miervaldis said. Evidence from Coburn’s research suggests the problem with the process starts from the very beginning. The application itself is lengthy and complex, requiring not only multiple stages of approval from different U.S. entities locally and stateside but also a long list of often hard-to-get components.

For instance, because the U.S. keeps no central database of contractors employed in locations like Afghanistan, the burden of proof of employment falls on the individual. Applicants are required to secure a signed letter of recommendation from their direct supervisor, which has proven difficult for those who are years out from their employment with the U.S. government. Writ large, lower-level or hourly contractors have found it difficult to even locate their former bosses to request the letter, Coburn said. Then, an applicant’s fate depends on whether the former supervisor even remembers them. “A lot of these guys worked for the U.S. government 10 years ago,” he said. “Imagine trying to get a signed document from your immediate supervisor who you haven’t worked for in 10 years.”

Of course, operating a bureaucratic system in the middle of a crisis doesn’t work. So Afghans who were cooperative with foreign governments are now trying to erase paper trails that would implicate them, burning documents and work badges and even getting rid of their digital footprints. It’s a complete mess in which Afghans will suffer most. That these embassies are supposedly doing the honorable thing to help fast-track visas for Afghan allies now that the country has been taken doesn’t show courage or generosity — it shows negligence, and will no doubt cost lives.

Do you have thoughts about this whole mess? Head to the comments section on the post or reply to this email.

TWEET OF THE WEEK

✨✨✨

SOME THINGS YOU MIGHT’VE MISSED

🔥 New York’s saying bye-bye to Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who resigned after a bombshell report confirming multiple allegations of sexual harassment. Here’s what his disgraced exit means for the Cuomo dynasty. | New York Times

🔥 A brief history of the Black-owned resorts that became holiday havens for professional-class Black Americans during the era of Jim Crow. | Harper’s Bazaar

🔥 Listen to this helpful explainer on the new doomsday IPCC report and how the climate crisis is playing out in real-time for vulnerable island countries like Madagascar. | Vox

🔥 New Zealand is going into total lockdown — after one man tested positive for COVID-19. | NPR

🔥 The total death toll in Haiti following the devastating 7.2-magnitude earthquake that hit the island country rose to 1,941 people, as of Tuesday evening. | Associated Press

🔥 French President Emmanuel Macron is under fire after his strong rhetoric about “irregular” flows of Afghan refugees into the country, which critics have labeled as pandering toward France’s right-wing. | Al Jazeera

🔥 Millions of Covid vaccine doses have been manufactured in a facility in South Africa yet Africans are still not receiving these vaccines because they’re getting shipped to Europe instead. | Guardian

🖊️ “HOW MUCH DOES IT PAY???” I wrote about my favorite resource for finding jobs and gigs: the hilarious @WritersofColor Twitter account which has been naming and shaming big publications for not being transparent about pay rates. | Nieman Lab

If you enjoyed this newsletter, check out more issues of The P Word here. Also, please consider subscribing (for free) if you haven’t yet!

Thanks so much for welcoming me into your inbox! If you liked this newsletter, please give it a ❤️ and share it with your friends, neighbors, and beloved pets.

Talk soon,

Natasha